December 19, 2015 by Pat Thomas

Americans are celebrating a moderate victory for GMO labelling this week.

The controversial Safe and Accurate Food Labeling Act (H.R. 1599), also known as the Deny Americans the Right to Know (or DARK Act) if passed, would have required labelling of GMOs to be overseen at a national level by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Regulating labelling at a national levels would have prevented individual States from implementing their own GMO labelling laws.

In addition, because the FDA is largely pro-GMO and opposed to labelling, there were fears that it would eventually lead to a weakening of mandatory federal labelling of GMOs which are already in place.

It sounds like success, but there are several twists in the tale and, of course, how the US – the world’s largest producer and consumer of GMOs – handles the issue of labelling affects us in the UK and the rest of the EU as well.

Over the last few years, powerful food and beverage organisations, who oppose GMO labelling have lobbied heavily and spent shocking amounts of money (by some estimates $100 million) to defeat individual States’ efforts to put GMO labelling laws on their books. Initiatives put to the vote in California, Washington, Oregon, and Colorado have fallen by the wayside, often by slim margins.

Every NGO involved in the GMO issue in the US has been fighting hard against this lobbying power with the most powerful resources they have – people.

A recent survey found that nearly 90% of US consumers want to know if their food contains genetically modified ingredients. Members of the public were encouraged to call and write their Representatives and Senators and encourage them to take the Act, which would have been attached as a ‘rider’ to a massive spending bill up for approval in the Senate, of the table.

In the end that’s what happened. The rider was not attached to the Omnibus Spending Bill – that’s the good news. The bad news is that the Dark act is not necessarily dead but could attached to another bill next year. The most likely, and from the point of view of the ‘other side’, tactically canny, candidate is the Child Nutrition Act (CNR) which is likely to be voted on in January.

If it happens this will be a tough battle. Advocacy groups around the US are gearing up campaigns to ensure that the CNR will continue to protect children from hunger and malnutrition through programs such as the National School Lunch Program, the School Breakfast Program and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC).

Should the DARK Act be attached as a rider to this bill it would likely pass – because what kind of a monster Senator would vote against a bill assuring adequate nutrition for children?

So what does this mean for Americans and how does it change the picture, if at all, for us in the UK?

Over the last couple of years many US states have tried to bring in laws for state-wide GMO labelling. The state of Vermont was the first state to succeed in passing such a law – though not without extraordinary opposition from biotech companies and the Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA) – a powerful lobbing force and the largest trade group for corporations that make food and beverages.

If it survives an ongoing legal challenge from the food industry that precedent-setting GMO labelling law takes effect in July 2016. Maine and Connecticut have also passed laws requiring labelling, but those measures don’t take effect unless neighbouring states follow suit.

Because the DARK Act may yet be voted in this is by no means a given.

This is depressing news for many US campaigning groups and consumers who would like to return focus to the bigger picture of GMOs – the fact that they are a symptom of a broken system, rather than an isolated problem. Big Biotech and Big Agriculture, with the help of powerful lobbies like the GMA, however, can afford to throw money at the labelling battle to keep everyone on the narrow track of this argument almost indefinitely.

Indeed, those who oppose GMO labels are continuing to do all they can to obscure the issue. Most recently the Grocery Manufacturers Association has proposed a SmartLabel that would add a bar code to foods that consumers can scan with their smartphone camera to get information about a product, including whether it contains GMOs.

The use of barcodes is of course entirely voluntary – so it changes very little in the landscape of consumer information. What is more the proposal fails to understand that not all shoppers have the time or inclination to use their smartphone (if they are even affluent enough to have one) to scan every product they buy to search for unlabelled GMOs.

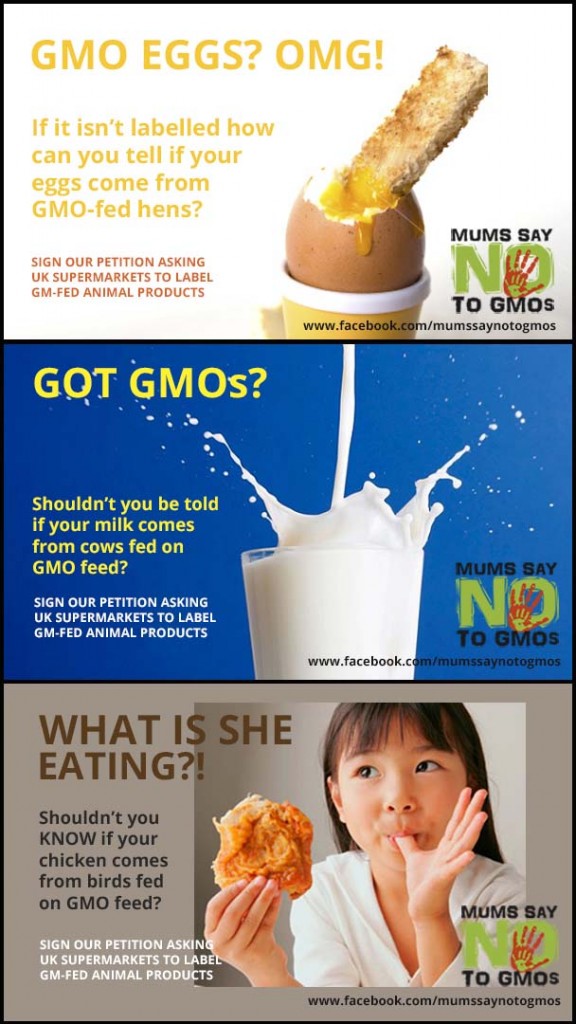

Many of the GMO foods we encounter in our supermarkets here are imports from the US. But this won’t always be the case; and, of course, many people are completely unaware that most of the meat, poultry, and dairy as well as some fish in the UK are fed on GMO feed.

Click here to sign the UK petition for supermarkets to label all GM-fed animal products

We tend to think of food products as GMO (either made from or containing genetically modified ingredients) or non-GMO (free from genetically modified ingredients).

In the EU US imports of GMO-containing foods are labelled. But labelling GM-fed animal products requires a different – and more difficult to articulate – label from these two options; one which covers the food products from non-genetically modified animals which are fed on GMOs.

In the US, none of the current draft State laws require GM-fed animals to be labelled and, EU regulators,likewise, do not feel that such labelling is necessary and in fact, the products of these animals could not be considered GM under any current definition.

With every regulatory agency suggesting that GM fed animals are no threat to human health, do we really need to label GM-fed animal products?

Many believe we do.

A normal animal, such as a cow, fed on a GMO diet will produce products like meat and milk which is not in itself GM (in other words there will be no basic DNA changes) but could still have other unexpected, unintended, added or deleted components that could lead to direct consequence or indirect consequences on our health.

For instance. it could contain elements that change our gut flora (which has widespread consequences for immunity, and physical and even mental well-being) or strange proteins which might make the food more allergenic.

For this reason it should be labelled, which is why we are happy to support the UK initiative by Mums Say No to GMOs, asking supermarkets to either stop selling GMO fed-animal products or label all such products that they sell.

With the arrival of the new GMO salmon, yet another wriggle has appeared in consumers’ need for labelling information: a genetically modified animal intended for direct human consumption.

The spectre of the new ‘frankenfish’ has made even those traditionally opposed to GMO labelling realise that denying people the right to know what it in their food is a tide that is going against them. Witness the turnaround by the New York Times editorial board which has now come out in support of labelling.

Ironically, the DARK Act rider attached to the Omnibus Spending Bill contained language, prohibiting the FDA from introducing any food that contains genetically engineered salmon until it publishes its final labelling guidelines.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that GMO salmon will be labelled – only that it won’t hit the shops until the FDA makes firm decisions about if, or how, to label it.

There are undoubtedly more obvious safety issues raised by the spectre of genetically modified animals intended for human consumption, simply because the process of altering the animal’s DNA can cause disruptions and unintended consequences to throughout the animal’s entire genome. To alert consumers to this would requires another very specific label.

But it is also possible that there could be a synergistic effect between the genetically altered animal and any GM feed it consumes. For instance, the animal may fail to thrive or grow less well than a normal animal; it may produce the strange proteins and changes in human gut flora mentioned above.

At the moment safety assessments do not take into account any possibility for such synergisms, nor do they look for direct or indirect human health consequences of consuming GM-fed animals. And of course, none of the four or five potential labels that a consumer might need to be truly informed about GMOs is mandatory – or even anywhere close to being implemented.

As with so much in the GMO fight, steps towards clarity can sometimes highlight greater complexity.

As more controversial GMOs – such as those made with synthetic biology, or computer generated DNA – come on stream they raise the spectre of still more specific warning labels.

The need for all these labels suggests that there is something very wrong with our food system.

Labelling – particularly warning labels – usually happens when people demand to know more, to be safer, and to be better informed. It ends up being driven by citizens because our politicians and regulators are lazy (and so often in the pocket of big business) and companies in the main do not practice transparency. Most would happily not tell us anything at all about the products they sell, how they are made or what the possible risks of using – or in this case eating – them is unless we as consumers demanded it.

Demands for GMO labelling hold a mirror up to the corporations that produce our food and remind them that there are consequences for their inaction and inattention to the GMO issue. Discussions around labelling are also an important part of the public education process on GMOs because they ground a complex subject in language, images and issues that are meaningful to most of us.

But labelling is a means to an end, rather than the end in itself. Labels can mislead as often as they inform – especially when they are voluntary and the ‘rules’ for that label are non-existent or poorly defined (as is the case with anything labelled ‘natural’).

The products we buy are becoming ever more crowded with label information which, as long as we read it, can certainly help us make better choices.

It would be simpler – and ultimately more productive for us all – to get GMOs out of the food system entirely. But until that is possible many see labelling as a way to make the best of a bad situation and to help keep consumers safe in the process.

Share this page

share using:

Or copy and paste this page address:

https://beyond-gm.org/gmo-labelling-the-battle-to-keep-corporations-honest/