October 10, 2016 by Brigid Armbrust

Vermont was the first US state to pass a law for mandatory labeling of GMO-containing foods. The state law was only in effect for a short time before it was overturned at the national level. Here, teen campaigner Brigid Armbrust, now 14, reflects on what motivated her to become involved in the Vermont campaign, on how it all panned out and on what the future holds.

It was early 2014. I was knitting my sweater in the Large Hearing Room at the Vermont State House, watching the Senate Judiciary Committee hear testimony on a bill, that if passed, would make my home state of Vermont the first state in the country to label genetically modified organisms in human food.

The Committee did not usually debate bills in the Large Hearing room, but their committee room was too small to hold the vast number of people who had shown up to watch. At that particular moment they were on speakerphone with a bio-tech representative in Washington, DC, who was urging them to reject the bill.

The man kept referencing the fact that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said GMOs were safe for human consumption. Then the chair of the committee, Senator Dick Sears, leaned close to the phone and said something like (I don’t remember the exact quote) “Just so you know, you’re talking to a room full of people who don’t put much stock in the FDA.”

Though this may sound like an insignificant moment in the huge story of the labeling movement, it is one of my favorite memories from that time.

Just a few months before, Senator Sears, along with most of the other senators on the Judiciary Committee, had been either more focused on the potential lawsuits Vermont might face from big agricultural companies if the bill passed, or relatively indifferent.

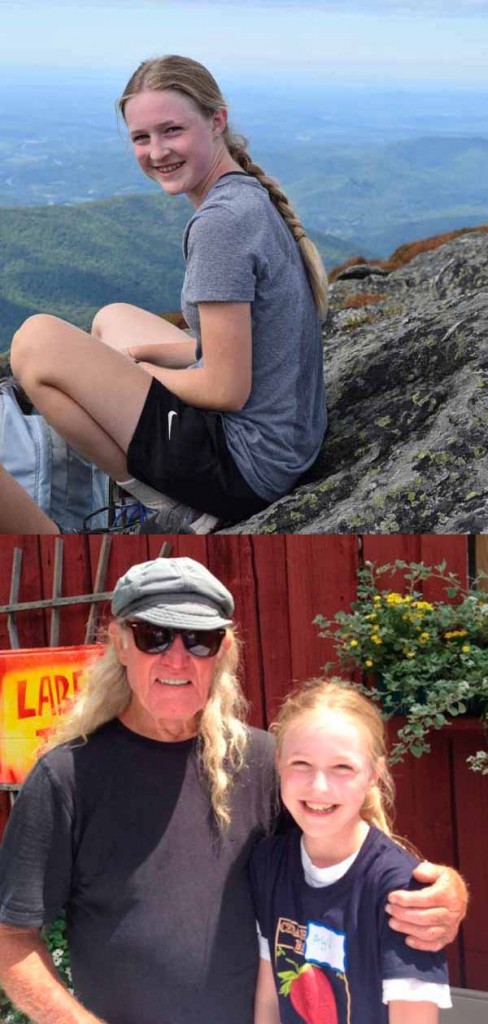

Then and now. 10 year-old Brigid Armbrust with campaigner Will Allen (bottom) at the height of the Vermont campaign, and today, age 14 (top).

Now they were all very supportive. They had been caught up in the enthusiasm of the movement. You could tell they enjoyed being part of it. They had stopped being stiff and unreachable politicians, and started being real people; people who were asking for change. I came to know many of the senators personally.

Soon afterward the bill passed the Judiciary Committee unanimously.

In the small state of Vermont, where I live, dairy is one of the major industries. The rocky and mountainous terrain makes cultivating crops difficult, but the endless fields of lush grass are perfect for livestock, such as cattle and sheep. For well over a hundred years, dairy cows grazed on the plentiful pasture land. Then, in the 1970s, the cows began to move inside.

Today, the majority of Vermont’s dairy cattle live in AFOs (Animal Feeding Operations) or CAFOs (Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations), large concrete buildings filled with rows of cows who may never feel the sun on their backs or the earth under their feet.

Many of these cows spend their entire lives inside. Some are injected with drugs to make them produce more milk.Meanwhile their pastures have been tilled under; the grass replaced with endless rows of the cheapest cow food in existence today: genetically modified corn.

More than 90% of the corn grown in Vermont for both livestock and human consumption is genetically modified. Farmers must drench these fields with hundreds of thousands of pounds of toxic pesticides such as atrazine, glyphosate, metolachlor, and simazine as well as synthetic nitrogen fertilizer, that then leach into and pollute Vermont’s waterways.

Industrial farming and its production and use of GM crops has negatively impacted Vermont in many ways. The conventional dairy farms in Vermont depend heavily on environmentally destructive farming methods such as pesticide use, synthetic fertilizers, and mono-culture. This system could not effectively function without genetically modified crops. GM crops are grown nation-wide, and what isn’t fed to animals or used to make biofuels finds its way onto our grocery store shelves. Approximately 75% of packaged food in America contains GM ingredients, the vast majority of which are still not labeled as such.

As the acreage of Vermont land planted with GM crops steadily increased, many Vermonters became concerned and saw labeling as a first step in addressing this issue.

In December 2011, Vermont organic farmer and activist Will Allen formed a coalition called Vermont Right to Know. This was a collaboration between Cedar Circle farm, VPIRG (Vermont Public Interest Research Group), Rural Vermont, and NOFA (Northeast Organic Farmers Association) Vermont. Though many Vermonter’s were concerned about the environmental impacts of GMOs as well as the potential health risks associated with consuming them (the FDA did no independent studies on GMOs before approving them for consumption), the main purpose of the coalition was to address the labeling issue.

To get people involved, the Vermont Right to Know coalition held a series of public meetings to teach people about the issue and what they could do about it. They got many people to email, call, or write letters to their representatives and senators.

It was after attending one of these meetings that I got involved.

On the way home from the meeting I was feeling frustrated and angry because it seemed there was nothing kids my age could do about this issue, which had suddenly become so important to me. Then I had an idea. With help from friends in the coalition, most importantly Cat Buxton and later Andrea Stander, I started a children’s letter writing campaign to support the labeling effort. We wrote to many people, including Governor Peter Shumlin, key senators on the Agricultural and Judiciary committees, the Commissioner of Health, and the Attorney General. Aside from this I also attended many protests and committee meetings, as well as debates and votes.

In May 2014, after a long struggle, the Vermont legislature passed a labeling law called Act 120, similar to the labeling laws in Europe. Many other states had tried and failed to do the same thing.

Why was Vermont able to do this when so many other states could not? The answer in my mind is simple. The Vermont State House is open to the public. Anyone can literally walk right in, find their senators or representatives and talk to them about issues that are important to them. You don’t even have to go through security. Put another way, in Vermont the legislature is actually hearing from their constituents, not just corporate lobbyists.

Even more important, in my opinion, was the positively gigantic grassroots movement that blossomed to support this issue. It was the thousands of Vermonters who took the time to call their representatives, write a letter to the editor of their local newspaper, or testify in front of a senate committee, that truly made it happen.

Vermont’s historic labeling bill is signed into law by Governor Shumlin as Brigid and her sister Molly (right) look on.

It was a beautiful thing to be part of; thousands of people banding together to ask for change, and achieving it against powerful (and wealthy) opposition. The big Ag companies tried everything. They sent lobbyists, sued Vermont, and tried to get the national legislature to ban labeling. Nothing worked.

I was standing next to Governor Shumlin when he signed Act 120 into law at a public ceremony on the steps of the State House. Looking out over that sea of happy, victorious faces; hearing the cheer rise up from them when the governor announced “It’s law.” was probably one of the most powerful things I have experienced in my life. It didn’t hit me until a few minutes later that I had just witnessed a historic moment; had a really great view of it, in fact.

But as the day approached when Act 120 would go into effect, another so called labeling “compromise,” the Roberts/ Stabenow Act, was introduced to the Senate in Washington D.C. This bill would “require” GM labels nation-wide in two years, but it would not be necessary for companies to print the information on the packages.

Instead they could supply 800 numbers to call, or QR codes to scan. There would be no penalties for noncompliance with the law. The law would also nullify all labeling laws then in effect, and make it illegal to pass anymore.

Despite much opposition from consumers, the Roberts/ Stabenow Act, or the DARK (Deny Americans the Right to Know) Act as labeling advocates call it, passed. Many people in congress had received campaign contributions from big Ag companies.

All in all, Vermont’s Act 120 was in effect for only a few weeks, but its influence was not nearly so short lived.

It has prompted some food companies (such as Mars and Campbell Soup) to begin permanent voluntary labeling. It has shown that passing labeling legislation is possible and disproved many myths, including the one that labeling will cause food prices to skyrocket. Most importantly it has forced big food companies to pay attention to us, forced them to hear our dissatisfaction with the way our food is labeled. Though Act 120 was eventually nullified, I do not believe it was a failure.

So, where do we go from here?

I believe we should try to strengthen the Roberts/Stabenow Act and transform it into something that looks a lot more like Act 120. It will be difficult, seeing as this is the corporate-influenced national government, not the small accessible Vermont legislature; but if it works this will end up being better than Act 120 ever was, as it will apply to the whole nation, not just Vermont.

However, as critical as the labeling movement is, it does not in any way solve the problems GMOs create, most notably environmental havoc.

In the Midwest, pesticide runoff from farms that grow GM crops leaches into the Mississippi River, polluting the drinking water of at least 18 million people. It then flows into the Gulf of Mexico, killing sea life and putting fishermen out of work.

In Vermont our waterways are polluted as well. The legislature often tries to figure out how to clean them up; most specifically Lake Champlain, which supplies drinking water to 145,000 people. However none of these plans effectively address the problem of degenerative dairy farming.

Vermont Right to Know coalition founder, Will Allen is currently working on these issues. He is trying to get Vermont companies, such as Cabot and Ben and Jerry’s, to get their milk from more environmentally sustainable dairy farms. He has gathered data on pesticide purchases and applications.

The records show steady increases in the use of both pesticides and synthetic fertilizers since GM crops were introduced to Vermont. Many of these pesticides are highly toxic, both to humans and the environment. Some are known to kill bees and butterflies, the pollinators that keep plants (and thus humans) alive. Synthetic nitrogen fertilizer, when leached into lakes, rivers and streams, creates toxic algae blooms which can destroy entire aquatic ecosystems.

For me, the real next step is far more complex than the GMO issue. Though I will continue to follow and work with it, it is no longer the only thing I am interested in. There are many other issues I wish to work on, including climate change, factory farming, the water crises, and other environmental and social problems facing my town, state, country, and planet.

In the end everything is connected, and solving any one of these problems without solving the others would not address the overall problem, that we are destroying our environment and thus ourselves. Put simply, I will continue to try to make the world a better place in every way I can.

You can do this too. Everyone, no matter how old they are, has within them the power to change the world. You just need to care about it enough. You also need to remember that everyone is human. Everyone, deep down within them, wants to do the right thing.

While protesting and angrily demanding change may seem easier, it is not the most effective method. Do not try to force people to change their mangled ways of thinking and acting. Instead, appeal to the human part of them, the part of them that wants to do right. Get to know them and understand why they think and act the way they do. Only then can you truly change them. You will also change yourself.

As kids, we have a special kind of power to create change. Though it may sometimes feel as though nobody cares about what we have to say, this could not be less true. When people see that kids care about certain issues, it intrigues them. They become curious and are more likely to take the time to learn about and help with those issues.

Also, adults do not get as defensive when listening to the ideas and opinions of children as they do when listening to those of other adults. They can therefore listen with an open mind and are more likely to seriously consider their concerns. Being a kid will not stop you from trying to fix the issues that matter to you. It will help you.

As I was leaving the Large Hearing Room that day, Senator Jeanette White made her way over to me. She said she’d noticed that I knit “the European way” and that she didn’t see people in America knitting that way very often. I said I thought it was way more efficient, but nobody else in my family would try it. They were too stuck in their inefficient, American way of knitting. She said everyone she knew was the same. Now, almost three years later I have still not finished my sweater (despite my “efficient” techniques).

Sometimes I like to think of the movement as a sweater. With Act 120 we were only casting on the stitches of a much bigger piece. Big Ag companies may have torn out a few rows, but we can always knit them back. It is a process, one we will be working on for a long time yet, and in the end it will really be about sewing all the different parts together to make one beautiful whole that will help protect us; not only from the cold, but from destroying the only home we have.

Winter is coming. Let’s all get to work on our sweater.

Selected Bibliography

It would be nearly impossible to cite all my sources, as I learned much of what I wrote here years ago. Here are some of my more important ones:

Share this page

share using:

Or copy and paste this page address:

https://beyond-gm.org/the-gmo-labeling-movement-vermont-and-beyond/